Three Types of Exercise Can Improve Your Health and Physical Ability

In an era defined by technological convenience and increasingly sedentary lifestyles, the human body exists in a state of profound mismatch with its evolutionary design. The consequences of this mismatch are stark and quantifiable.

Physical inactivity has emerged as a silent pandemic, identified as the fourth leading risk factor for global mortality and a primary driver of chronic disease worldwide. It is responsible for an estimated 3.2 million deaths globally each year. The challenge, however, is not merely to move more, but to move with intelligence and purpose.

The global health crisis of inaction necessitates a clear, evidence-based framework for understanding and implementing effective exercise. While the general benefits of activity are widely acknowledged, a deeper understanding reveals that a truly robust state of health and functional ability cannot be achieved through a single mode of training.

The purpose of this report is to move beyond simplistic prescriptions and provide a definitive guide to these three pillars. It will explore the unique scientific underpinnings, physiological mechanisms, and profound health benefits of each.

- Powers cardiovascular system

- Burns fat efficiently

- Enhances endurance

- Reduces chronic disease risk

- Builds muscle mass

- Strengthens bones

- Boosts metabolism

- Enhances functional ability

- Improves range of motion

- Prevents falls & injuries

- Enhances coordination

- Maintains independence

Moderate-Intensity

Vigorous-Intensity

Moderate or Greater Intensity

Legs, Hips, Back, Chest, Core, Arms

The First Pillar: Aerobic Conditioning – The Engine of Vitality

Aerobic conditioning, often referred to as cardiovascular or “cardio” exercise, serves as the foundational pillar for systemic health. It is the engine that powers every other physical capacity, governing the body’s ability to produce and sustain energy,

deliver vital nutrients, and maintain the intricate balance of its internal systems. Understanding its mechanisms and benefits is the first step toward building a truly resilient and vital human machine.

A. Defining Aerobic Exercise: The Science of Oxygen

At its core, aerobic exercise is defined as any form of sustained physical activity that utilizes large muscle groups, increases the heart rate, and elevates breathing for an extended period. The term “aerobic” literally means “with oxygen,” which points to the primary metabolic pathway engaged during these activities.

When performing exercises like brisk walking, running, swimming, or cycling, the body’s demand for energy escalates. To meet this demand, the cardiorespiratory system—the heart, lungs, and blood vessels—works harder to draw in more oxygen and deliver it to working muscles.

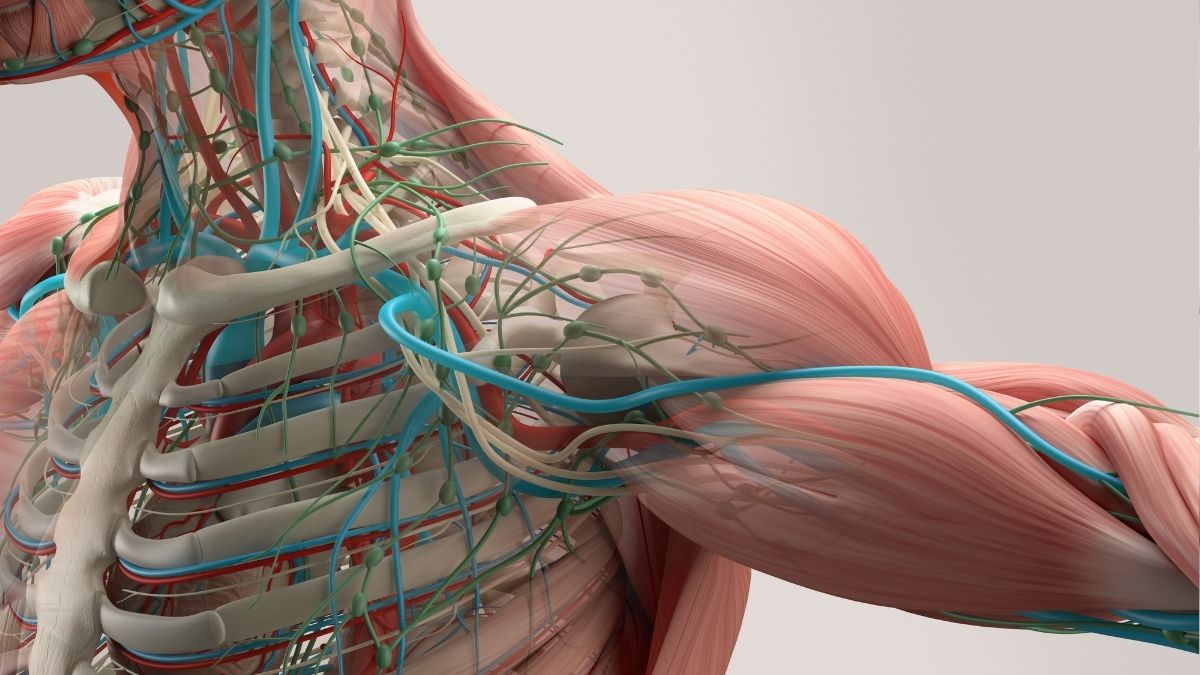

B. The Physiological Cascade: Remodeling Your Internal Systems

Consistent engagement in aerobic activity triggers a cascade of profound physiological adaptations that fundamentally remodel the body’s internal architecture for greater efficiency and resilience. The most direct impact is on the heart itself. Like any muscle, the heart adapts to the stress of exercise by becoming stronger and more efficient.

The left ventricle, the heart’s main pumping chamber, increases in size and strength, allowing it to pump a greater volume of blood with each beat (a phenomenon known as increased stroke volume).

C. Systemic Health Benefits: A Shield Against Chronic Disease

The systemic adaptations spurred by aerobic conditioning translate into a powerful defense against a wide spectrum of modern chronic diseases. A robust body of epidemiological evidence confirms that regular aerobic activity is one of the most effective strategies for preventing and managing cardiovascular diseases.

It significantly lowers the risk of heart disease and stroke by improving key biomarkers of health. These mechanisms include lowering blood pressure (hypertension), improving blood lipid profiles by increasing levels of high-density lipoprotein ($HDL$, or “good” cholesterol) while decreasing levels of low-density lipoprotein ($LDL$, or “bad” cholesterol) and triglycerides, and enhancing the health and elasticity of blood vessels.

E. Actionable Protocols: Putting the Science into Practice

To translate the science into tangible results, public health organizations have established clear, evidence-based guidelines. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that adults engage in at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity per week, or an equivalent combination of both.

- Moderate-intensity activity noticeably raises the heart rate and breathing. A practical way to gauge this level is the “talk test”: one should be able to carry on a conversation, but not sing a song. Examples include brisk walking, cycling on level ground, swimming at a leisurely pace, and water aerobics.

- Vigorous-intensity activity causes rapid breathing and a substantial increase in heart rate. During this level of activity, one would only be able to speak a few words at a time. Examples include running or jogging, swimming laps, cycling at a fast pace or on hills, and high-intensity interval training (HIIT).

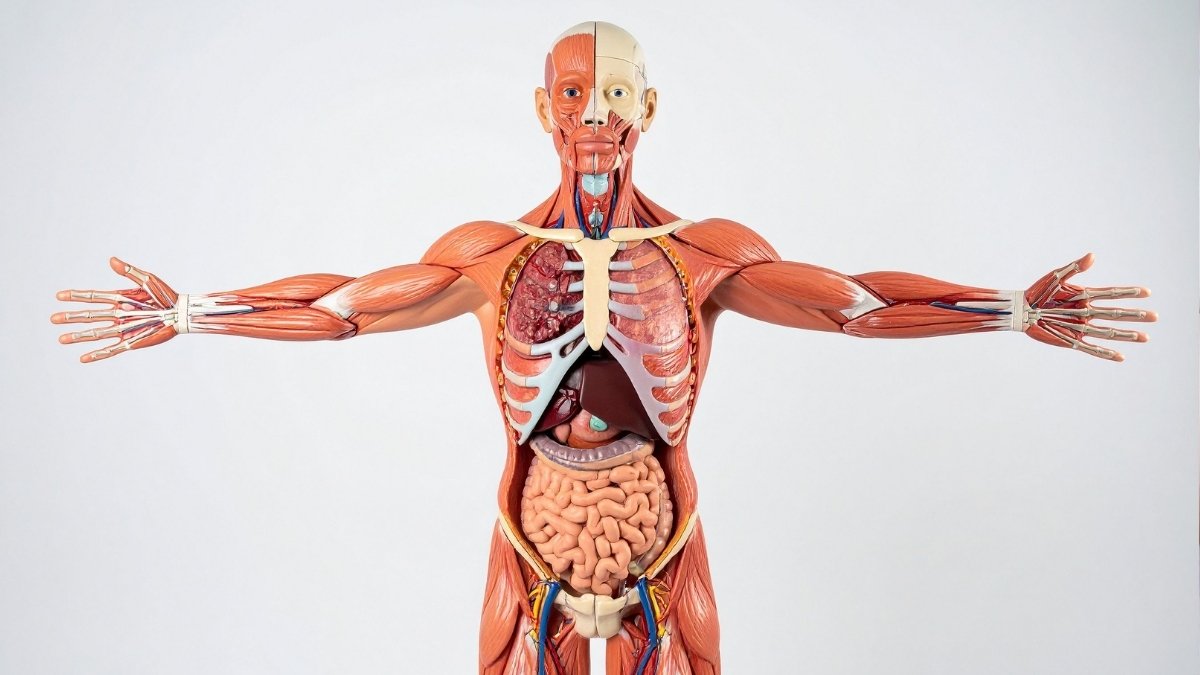

The Second Pillar: Resistance Training – Building a Resilient Framework

If aerobic conditioning is the engine of the body, resistance training is the chassis and framework. It is the pillar responsible for building and maintaining the structural integrity of the human form—our muscles, bones, and connective tissues.

Historically associated primarily with athletic performance and aesthetics, a modern understanding reveals strength training as a cornerstone of metabolic health, functional independence, and long-term resilience against the challenges of aging.

A. Defining Strength Exercise: The Principle of Overload

Strength, or resistance, exercise encompasses any physical activity designed to make muscles work against an opposing force or weight.

This resistance can be generated by a variety of sources, including free weights (dumbbells, barbells), weight machines, elastic resistance bands, or even one’s own bodyweight through exercises like push-ups, squats, and pull-ups.

B. The Architecture of Strength: Muscle, Metabolism, and Bone

The physiological adaptations to resistance training are profound and multifaceted, extending far beyond the target muscles. The most visible outcome is muscle hypertrophy, the process by which individual muscle fibers increase in size. When subjected to the mechanical tension of resistance exercise, muscle fibers sustain microscopic damage or “micro-tears.”

This increase in lean muscle mass has a powerful effect on the body’s metabolic rate. Muscle tissue is metabolically active, meaning it requires energy (burns calories) simply to maintain itself, even at rest. A body with a higher percentage of muscle mass has a higher resting metabolic rate (RMR). This effectively turns the body into a more efficient calorie-burning engine, operating 24 hours a day.

C. Functional Strength for Daily Life: From the Gym to the Grocery Store

The true value of this pillar lies in its direct translation to “physical ability” in the real world. Functional strength is the capacity to perform the tasks of daily life safely and effectively.

The strength built in a controlled setting directly enhances one’s ability to carry heavy bags of groceries, lift a child without straining one’s back, move furniture, or perform yard work. For an aging population, the stakes are even higher.

D. Actionable Protocols: A Blueprint for Building Strength

To harness these benefits, the CDC’s physical activity guidelines recommend that adults perform muscle-strengthening activities of moderate or greater intensity that involve all major muscle groups on 2 or more days a week. Major muscle groups include the legs, hips, back, abdomen, chest, shoulders, and arms.

A comprehensive program does not require a gym membership and can be adapted to any fitness level or equipment availability:

- Free Weights and Machines: The traditional approach using dumbbells, barbells, and selectorized machines is highly effective for isolating and overloading specific muscle groups.

- Resistance Bands: These are portable, versatile, and excellent for providing variable resistance through a range of motion.

- Bodyweight Exercises: Foundational movements like squats, lunges, push-ups, and planks are highly effective and can be modified to increase or decrease difficulty, making them accessible to everyone.

The Third Pillar: Flexibility & Balance – The Foundation of Control and Longevity

Often relegated to a brief cool-down or overlooked entirely, the third pillar of fitness—encompassing flexibility and balance—is a co-equal component essential for functional movement, injury prevention, and the preservation of a high quality of life.

It represents the body’s control system, ensuring that the power generated by the muscular system and the endurance provided by the cardiovascular system can be expressed with precision, safety, and efficiency.

A. Defining the Pillar: Suppleness and Stability

This pillar is composed of two distinct but related components, both of which are recognized by organizations like the ACSM as integral to overall fitness:

- Flexibility is defined as the available range of motion of a joint or a series of joints. It is the ability of the soft tissues—muscles, tendons, and ligaments—to lengthen and allow for unimpeded movement. Adequate flexibility is necessary for performing everyday movements, from reaching for an object on a high shelf to bending down to tie one’s shoes, without strain.

- Balance is the ability to maintain the body’s center of mass over its base of support. It can be static (e.g., standing on one leg) or dynamic (e.g., walking on an uneven surface). Balance is not a passive state but an active process requiring constant, minute adjustments based on sensory feedback.

While distinct, these two qualities are interdependent. For example, restricted flexibility in the ankles or hips can compromise one’s ability to make the necessary postural adjustments to maintain balance.

B. The Bulwark Against Injury and Aging: A Matter of Life and Limb

The practical implications of a well-trained control system are most evident in injury prevention and healthy aging. For older adults, maintaining balance is a matter of life and limb. Falls are a leading cause of fatal and non-fatal injuries in this demographic, often triggering a cascade of health complications, loss of confidence, and a decline in independence.

The evidence for the efficacy of balance training is compelling; targeted exercise interventions have been shown to reduce the risk of falls by as much as 30% in older adults. This single statistic represents the prevention of countless fractures, hospitalizations, and life-altering events.

C. Actionable Protocols: Integrating Control into Your Routine

Integrating this pillar into a fitness routine can be accomplished through a variety of accessible and beneficial practices:

- Static Stretching: This involves holding a stretch in a challenging but comfortable position for a period, typically 15-30 seconds. It is most effective when performed after a workout when muscles are warm.

- Dynamic Stretching: This involves active movements that take a joint through its full range of motion, such as arm circles or leg swings. It is an excellent way to prepare the body for more intense activity and is often incorporated into a warm-up.

- Dedicated Practices: Disciplines like Yoga, Pilates, and Tai Chi are particularly effective because they holistically integrate flexibility, balance, strength, and body awareness. These practices are also a form of “mindful movement.” The intense focus required to hold a challenging yoga pose or flow through a Tai Chi sequence is also a potent form of cognitive training.

D. The Synergy of Synthesis: Integrating the Three Pillars for Optimal Human Function

While each of the three pillars offers a distinct and powerful set of benefits, their true value is realized when they are no longer viewed as separate entities but as components of a single, integrated system. The human body does not operate in silos; it is an interconnected web of systems where the function of one part profoundly influences all others.

A truly effective fitness program mirrors this reality, strategically weaving together aerobic, strength, and flexibility/balance training to create a whole that is far greater than the sum of its parts.

A. The Interconnected System: How Each Pillar Supports the Others

The relationship between the three pillars is not just complementary; it is mutually reinforcing. Each pillar enhances the performance and safety of the others, creating an upward spiral of fitness and capability.

- Aerobics Supports Strength and Flexibility: A well-developed cardiovascular system, cultivated through aerobic conditioning, improves the body’s ability to deliver oxygen and nutrients to muscle tissue. This enhanced circulation not only fuels performance during a demanding strength training session but also accelerates the recovery process afterward by more efficiently clearing metabolic waste products.

- Strength Supports Aerobics and Balance: A strong musculoskeletal framework, built through resistance training, is the foundation for efficient and injury-free movement. Strong core muscles provide stability for the torso, improving running form and economy.

- Flexibility & Balance Support Aerobics and Strength: An adequate range of motion in key joints, maintained through flexibility work, is crucial for proper biomechanics in virtually all other forms of exercise.

- It allows an individual to perform a squat or lunge through its full depth, maximizing muscle activation and minimizing stress on the spine.

B. A Blueprint for a Balanced Week: From Theory to a Personal Plan

Integrating these three pillars does not require spending countless hours in a gym. A well-structured weekly plan can efficiently incorporate all components in alignment with established public health guidelines. The following is a sample schedule designed to demonstrate how this integration can be achieved:

- Monday: Moderate-Intensity Cardio (30-minute brisk walk or jog) followed by 10 minutes of full-body static stretching.

- Tuesday: Full-Body Strength Training (targeting all major muscle groups with exercises like squats, push-ups, rows, and overhead presses).

- Wednesday: Vigorous-Intensity Cardio (20-minute HIIT session) or Active Recovery (60-minute Yoga class, which covers flexibility and balance).

- Thursday: Full-Body Strength Training (using different exercises or variations from Tuesday’s session).

- Friday: Moderate-Intensity Cardio (45-minute bike ride or swim).

- Saturday: Active Recreation (e.g., a long hike, playing a sport) or a dedicated Flexibility/Balance session (e.g., a Tai Chi or Pilates class).

- Sunday: Rest and recovery.

This balanced approach ensures that the body is consistently challenged across all domains of fitness, promoting holistic adaptation and minimizing the risk of overuse injuries associated with specializing in a single activity.

Conclusion:

The evidence is unequivocal: a comprehensive approach to physical activity, built upon the three pillars of aerobic conditioning, resistance training, and flexibility/balance, is one of the most powerful tools available for enhancing human health and functional ability. Optimal well-being is not the product of a singular focus on running, lifting, or stretching, but rather the emergent property of their intelligent and consistent integration.

This report has sought to reframe the conversation around exercise, moving it away from a narrow focus on aesthetics or disease statistics and toward the more holistic and empowering pursuit of “Physical Competence.” Adopting a balanced training program is not a short-term fix or a burdensome chore; it is a proactive, lifelong investment in one’s own capability.